What does the Constitution say about foreign policy? In this free resource, explore how the powers of Congress and the president protect and advance the country’s interests abroad.

Last Updated May 19, 2023

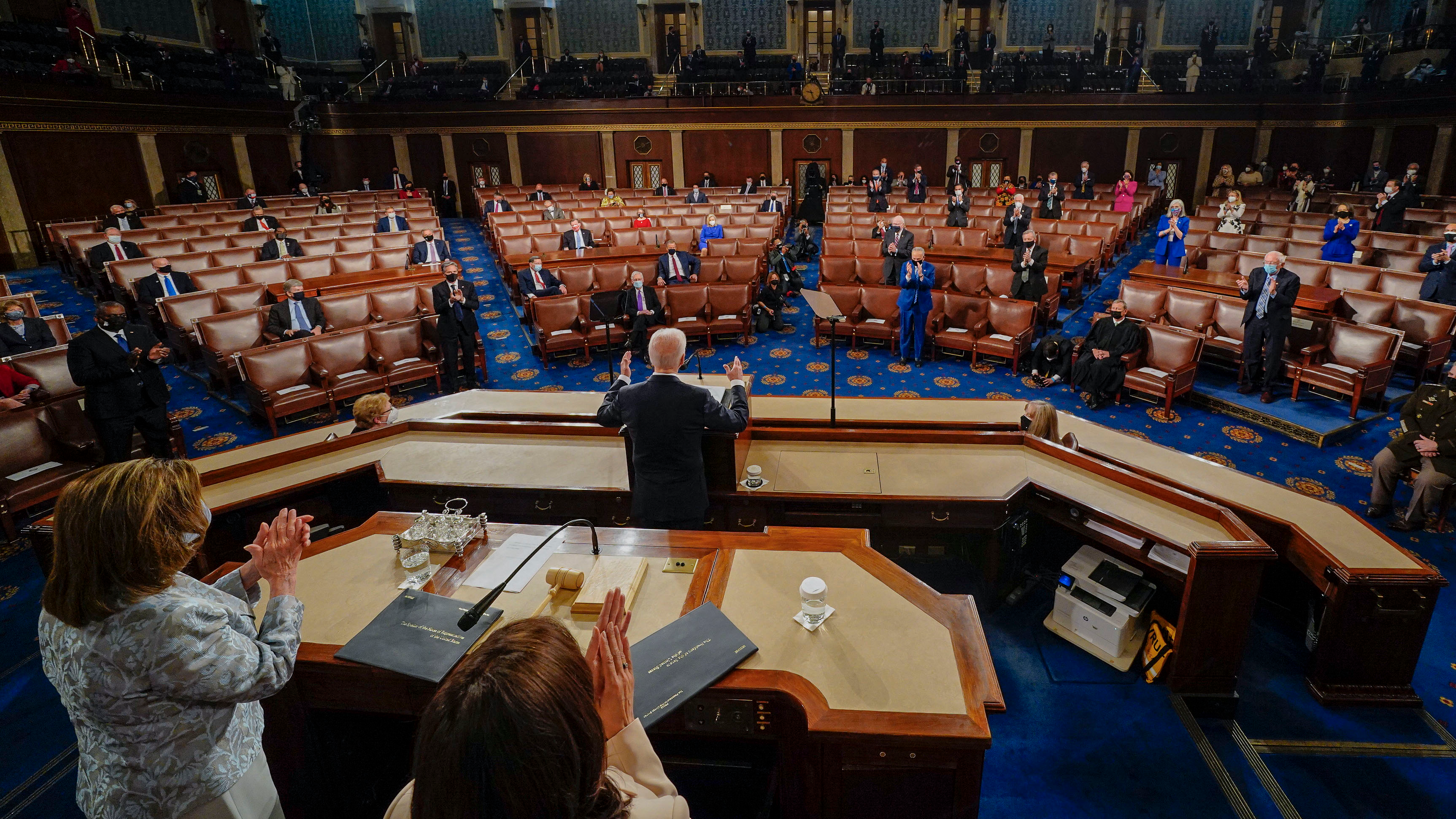

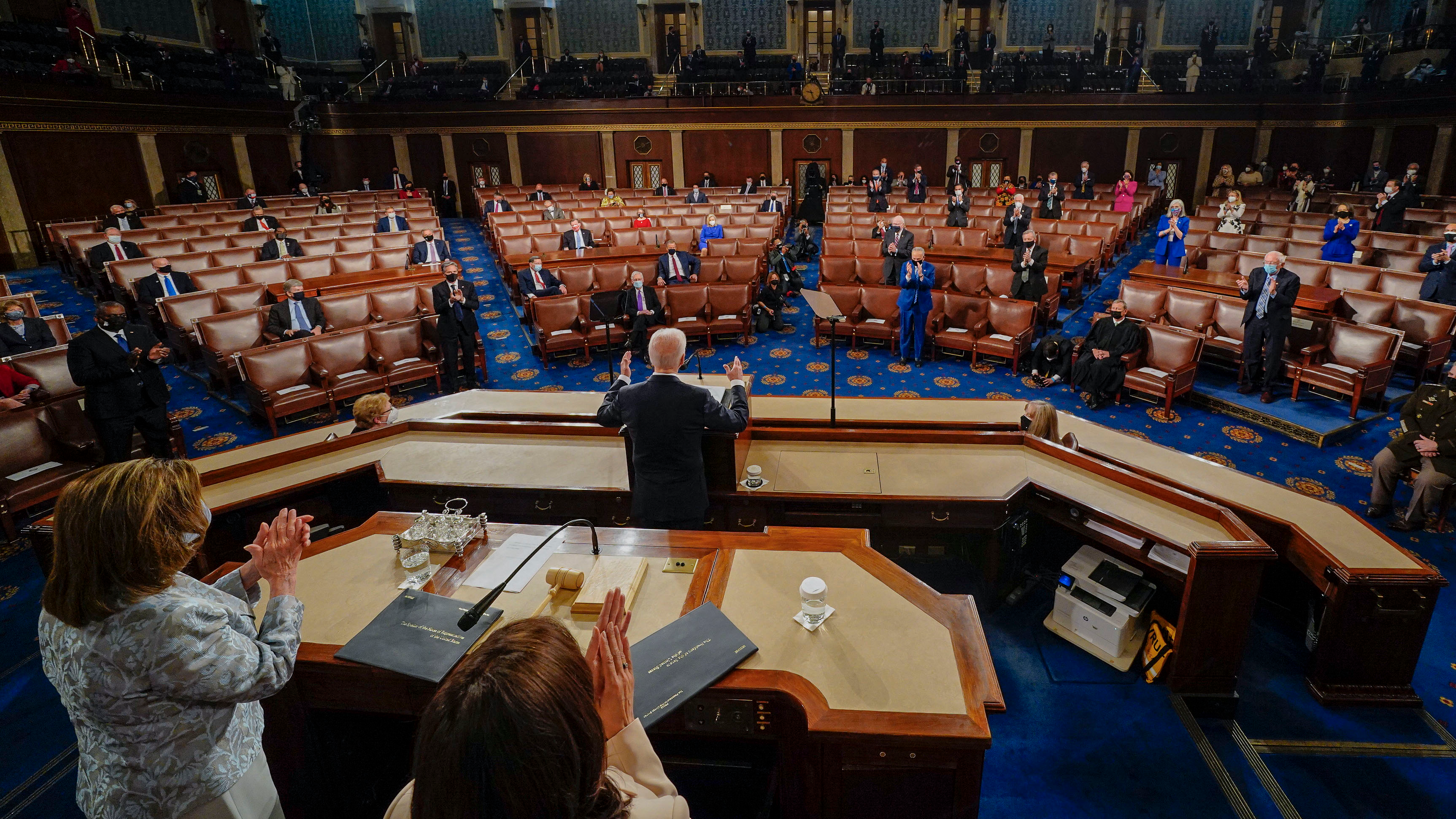

President Joe Biden addresses a joint session of Congress, with Vice President Kamala Harris and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi on the dais behind him at the US Capitol in Washington, DC, on April 28, 2021.

Source: MELINA MARA/POOL/AFP via Getty Images

On July 10, 1919, President Woodrow Wilson walked into the Senate chamber with a document under his arm: the Treaty of Versailles. That occasion marked the first time in 130 years that a president personally delivered a treaty to the Senate floor.

The document reflected Wilson’s vision for a peaceful global order following World War I, and he had spent the past six months negotiating its conditions in France. If approved, it would have brought the United States into the League of Nations, a new intergovernmental organization founded on the idea that security threats to one member demanded responses from all members.

On the Senate floor, Wilson called for the chamber’s approval: “The stage is set, the destiny disclosed. It has come about by no plan of our conceiving, but by the hand of God. We cannot turn back. The light streams on the path ahead, and nowhere else.”

But Wilson’s big dreams for world peace crashed into harsh realities. Despite his advocacy, the Senate voted against the treaty, fearing the potential entanglements and obligations of membership associated with joining the League of Nations. Who would the United States be required to defend and at what cost?

The humbling episode was far from the only time Congress has rebuffed a president’s foreign policy agenda. In fact, the executive branch, led by the president, and the legislative branch, led by Congress, periodically clash, in part by constitutional design, on issues such as using military force and signing international agreements. However, that relationship has changed over time, and, since the end of World War II, the president has frequently had the upper hand in shaping the country’s foreign policy.

In this resource, we’ll explore what the Constitution says about making foreign policy and how foreign policymaking is actually carried out today.

Although the U.S. Constitution is arguably the country’s most important document, it’s not particularly long. In fact, the original text clocks in at only 4,543 words—approximately the length of a twenty-page essay, double spaced.

As a result, the Constitution doesn’t provide instructions for how to handle every conceivable foreign policy situation. Instead, it sets general guidelines and splits foreign policy–making responsibilities between the executive and legislative branches. Some of those responsibilities are clearly and explicitly stated, while others are implied and have been interpreted differently over the years.

The Constitution gives Congress several enumerated, or expressly granted, powers:

The Constitution gives the president several enumerated powers in foreign policy as well:

Although the Constitution assigns certain enumerated powers to the president and Congress, many of those powers overlap and conflict. As a result, a tug-of-war periodically ensues over the country’s foreign policy agenda.

That tension has been a defining feature of U.S. foreign policy since the country’s founding. For instance, President George Washington and Congress clashed in 1793 over whether to take sides in a conflict between Britain and France.

Let’s explore what the division of foreign policy responsibilities looks like today.

Military operations: Although presidents have command over the military, they must notify Congress within forty-eight hours of sending troops abroad according to the War Powers Resolution. If Congress fails to authorize the military action, presidents are required to withdraw troops within sixty days, with a possible one-time extension to ninety days. Congress passed the War Powers Resolution to ensure that presidents can act effectively in a military context by deploying troops quickly, though not without Congress’s eventual approval. However, past presidents have violated the War Powers Resolution without facing action from Congress. For example, President Barack Obama ignored the War Powers Resolution when intervening in Libya in 2011, arguing that the U.S. involvement fell short of full-blown hostilities, thus not requiring invoking the act.

International agreements: According to the Constitution, the Senate can approve, reject, or sit on (not take action on) treaties. However, in recent decades, presidents have circumvented the Senate and struck bilateral and multilateral agreements with other countries on their own authority. Although that process provides presidents greater latitude to join international treaties, such agreements are not binding commitments under U.S. law, and future presidents can easily reverse them.

Immigration: Congress can pass legislation setting the United States’ immigration policies. The president’s job is to execute those laws; however, they can also advance their own agenda in certain ways. For instance, in 2011 Congress failed to pass Obama’s DREAM Act, which would have permanently protected immigrants who arrived in the United States as children. In response, Obama issued an executive action that deferred deportation for those individuals. However, Obama’s action was ultimately litigated and ruled unconstitutional.

Intelligence: The president nominates the heads of all intelligence agencies such as the FBI and the CIA and approves all covert action or classified foreign missions. However, committees within the House and Senate oversee those intelligence agencies, and Congress has the power to set their budgets.

Trade: Congress approves every significant trade deal between the United States and foreign countries. However, Congress has, at times, delegated certain trade powers to the president. For example, since 1974, it has enacted various time-limited legislation that grant the president the power to negotiate trade deals before they are put to a congressional vote.

Foreign aid: Executive branch agencies—such as the State Department, Department of Defense, and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID)—distribute foreign aid. However, Congress determines how much funding each agency receives through its approval of the federal budget. In the past, Congress has also intervened directly in the provision of aid—for instance, by passing legislation that withholds aid from governments with poor human rights records.

Since the end of World War II, presidents have exercised enormous latitude in using military force, forging and breaking international agreements, and conducting diplomacy. Although the president and Congress split foreign policy responsibilities, most scholars agree that the balance of power today skews decisively toward the president for five principal reasons.

Constitutional authority: This authority specifically refers to the powers given to Congress and the president in the Constitution and as a result of its interpretation through time, practice, and Supreme Court rulings. The president’s responsibilities include leading diplomatic efforts and serving as commander in chief.

Statutory authority: This authority refers to the powers assigned to a government official or agency through legislation passed by Congress. In many instances, Congress has delegated foreign policy powers to the executive branch in an effort to empower presidents to act effectively. Presidents often interpret those delegated powers in ways Congress did not originally intend. For example, Congress passed the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF), which gave the president sweeping power to pursue the perpetrators of the 9/11 terrorist attacks and their supporters. More than two decades later, the AUMF is still being used to justify military action in Iraq and Syria against the self-proclaimed Islamic State, a terrorist group that didn’t even exist at the time of the 9/11 attacks.

Veto power: Although this power is rarely exercised over foreign policy issues, presidents can veto any legislation passed by Congress. Congress can override a presidential veto with the support of two-thirds of their members, but it has only done so in less than 5 percent of all vetoes. The daunting odds of overriding a presidential veto can deter Congress from trying to legislate foreign policy in the first place.

Presidential initiative: In the past, presidents have taken unilateral actions without consent or approval from Congress under the assumption that Congress would be unable to organize a response due to partisan splits or other reasons. In many instances, those unilateral actions have been executive orders—presidential declarations that carry the force of the law but do not require congressional approval. Using executive orders in foreign policy has its limitations. For one, subsequent administrations can easily undo a predecessor’s executive order. In fact, in the first hundred days of President Joe Biden’s tenure, he reversed almost 30 percent of his predecessor’s executive orders.

Judicial intervention: When Congress and the president disagree over power and purview, the third branch of government—the judiciary—can arbitrate. However, the Supreme Court has shown reluctance at times to make such rulings. For example, the Supreme Court declined to hear a case in 1979 regarding former President Jimmy Carter’s right to end a mutual defense treaty with Taiwan without congressional approval. As a result of the court’s silence, Carter could continue his policy.

Although foreign policy–making power favors the president today, Congress is far from impotent. It can shape public opinion on foreign affairs by holding public hearings and investigations as it did during the Vietnam War and the Iran-Contra Affair. Additionally, congressional consensus is often required to prompt substantial action on an issue. For example, the United States rejoined the Paris climate accords in 2021 through an executive order, but in order to meet any of the agreement’s goals, Congress must pass legislation implementing major environmental policies, which has proven difficult, though some, such as the $500 billion dollar Inflation Reduction Act, have passed. Congress can also pass legislation to curtail a president’s powers or reprimand them for overstepping their authority. However, in recent decades, partisan division has frequently prevented Congress from reaching consensus on many issues—including foreign policy—making it difficult to pass legislation.

Congress’s influence over foreign policy is greatest when presidents require its action, such as with issues of trade, budget appropriations, and domestic legislation. Conversely, Congress’s influence is weakest when the president is widely regarded as empowered to act unilaterally, such as when negotiating and deploying military forces. Congress also struggles when its authority is disputed—as with initiating major interventions—in part because it can only succeed by overcoming a presidential veto.

Congress and the president play distinct and important roles in setting and executing U.S. foreign policy. Although the president holds the lion’s share of the power today, history has shown that the relationship between those two branches of government is constantly evolving.